Steve Toth with his 1936 Model 37 Dobro

SJ: How did you get started playing the dobro? Who or what inspired you to start playing?

ST: When I was growing up, my father loved country and western music and he would listen to it all the time on the radio so naturally I would hear it too. My parents would also take the family on vacations to a dude ranch each summer and I would hear country music there. Back then, in the mid 1950’s, when I was about 12 or 13 years old, they would play bluegrass music on the country station in the New York area where I grew up. They played the bluegrass performers right along with the country artists like Hank Williams, Kitty Wells, Hank Snow, Ray Price, etc. since in those days bluegrass was still simply a part of country music. And two groups I would hear frequently had dobro in their music – the Osborne Brothers and Flatt &Scruggs. That was my initial exposure to the dobro. Then, every once in a while Flatt & Scruggs would do a show in our area and my parents would take my brother and I to see them and that’s when I got to see Uncle Josh Graves for the first time. Wow, was he terrific! Seeing him in person really lit the flame in me for the dobro or the “old hound dog“ guitar as Lester Flatt would call it when he introduced Josh!

Josh Graves with his 1935 Model 27 Dobro (from DOBRO ROOTS)

SJ: How did you learn to play? Did you take formal lessons or were you self-taught? Looking back, what were the things that were most helpful in learning to play the dobro?

ST: I picked up the Flatt & Scruggs LP record album called Foggy Mountain Banjo which had great dobro on it by Uncle Josh and an Osborne Brothers LP album, I think it was called Country Pickin’ and Hillside Singin’, which also had a lot of dobro on it. I later learned that it was Shot Jackson playing dobro on that album but I didn’t have any idea who it was at that time. I would also buy Flatt & Scruggs 45 rpm records with their early hits on them. So, it was from those early records that I taught myself to play the dobro in the late 1950’s.

Original Dobro catalog cut – “California 5 Series” – From DOBRO ROOTS

SJ: What model was your first dobro? In addition, it’d be great if you could give us an idea of the different kinds of dobro brands and models that were available when you got started.

ST: My first “dobro”was actually a National Tricone! My father got it for me from a music store he knew about and that was all they had available so he bought it. I played it for a short time but it just didn’t have the volume and tone for bluegrass style picking so we returned it to the store. That was a big mistake! It cost less than $100 at the time and in later years it would have risen in value to a few thousand dollars. Since we were not aware of any stores or anyone in the New York City area that had a dobro for sale, I ended up with a National Duolian with a warped neck and broken neck heel. But, with a high nut on it, it played OK and had pretty good volume. We got it in Upstate New York and I still have it! I played that until around 1972 when I got my first real “Dobro”, a 1930 Model 55.

Mike Auldridge with his 1936 Model 37 Dobro made by Regal (from DOBRO ROOTS)

There was basically nothing available as far as dobros were concerned where I lived in the mid to late 1950’s. I was certainly not aware of anything and even now the history of the dobro during that period is still quite vague. I’m sure there were many prewar Dobro’s out there somewhere –under beds, in closets, in attics, in barns –but they would not surface for many years to come. It may have been the folk music boom of the early 60’s and then the Flatt and Scruggs appearances on the Beverly Hillbillies TV Show that made many people aware of what they, their parents or grandparents had. But there was still relatively no market for them so they stayed where they were stashed away.

From 1933 Dobro catalog cut – “California 6 Series”

SJ: How/when did you start building a collection of prewar Dobro’s? Did you start out to become a collector or did that evolve over time? I’d also be curious to know what the market looked like when you got started vs. the way it is today. In other words, how has the value of prewar Dobro’s changed over time?

ST: I once said I would never collect prewar Dobros because it took me about 15 years to find just one for sale. But as the years went by, more and more prewar Dobros came on the market for sale but there were very few buyers. I wish I had started collecting in the 70’s when the values were in the $300 to $600 range. But, alas, I didn’t start actually collecting until around the year 2000. I happened to meet someone who had about 10 prewar Dobros in his collection and he couldn’t even play the Dobro! So I decided that it would be alright if I started collecting them too since I always had a love for them. And it was only possible because of the Internet. I would never have had access to the number of instruments I was able to see on the Internet which were up for sale at any time without that resource at my disposal. I decided to start by looking for one of each model made in the prewar period focusing on the wood body Dobros with the round screens. I was also looking for ones that sounded good too, if possible. In the case of the rare models sound was of less importance. I started to find that the lower end models like the Model 27 and Model 37 seemed to have a better sound than the higher end walnut models. This confirmed what Bobby Wolfe had said in his great articles about the Model 27 Dobros. I would also work on setting up each Dobro to sound the best I could get it since most were poorly set up when I got them. I would also try modern cones in them and experiment back and forth with the original and modern cone. I found that, in most cases, a good modern cone tended to improve the sound, to my ears, by adding more low end and generally more volume. I always felt that changing a cone did not hurt the originality of a prewar Dobro anymore than changing out a calf skin head in a prewar Mastertone banjo for a modern plastic head, which is universally done, lessens the value and collectability of a prewar Mastertone banjo. It was more about which sounded the best to me. Of course, I would keep the original cone so it could be re-installed at a later date if I wanted to. By the time I started collecting prewar Dobros the values had increased to roughly the $1,000 to $2,000 range and up. However, over the last several years the prices of prewar Dobros and most vintage instruments, in general, have come down a bit.

Jerry Douglas with his 1936 Model 37 Dobro made by Regal (from DOBRO ROOTS)

SJ: Your most recent book – DOBRO ROOTS – is the most comprehensive pictorial history/reference for wood-bodied pre-war Dobro’s ever published. In his foreword to the book Jerry Douglas hit the nail on the head when he referred to your book as the “Dobro Wish Book.” Now that Jerry is touring with the Earls of Leicester he’s returned to playing his prewar Dobro through a microphone. Not that the two are causally related but the combination of the two have certainly piqued interest in prewar Dobros! From a player’s perspective, how do you think about the difference between prewar Dobros and guitars made by contemporary builders like Paul Beard, Kent Schoonover and Tim Scheerhorn? What are the pros and cons of playing prewar Dobros vs. a modern style instrument?

DORBO ROOTS – A Photo Tour of Prewar Wood Body Dobros

Click here to purchase a copy of DOBRO ROOTS from Elderly Instruments

ST: Thank you for the kind words about “DOBRO ROOTS”! And I, once again, want to thank my good friend, Jerry Douglas, for taking the time to write such a wonderful Foreword for the book. I would also like to thank my good friend, Larry Maltz, with his broad knowledge of prewar Dobros for his assistance on many aspects of the book.

It’s interesting that when I started the book I had not even heard of the Earls Of Leicester or Jerry’s involvement with that great group. The Earls do a fantastic job of recreating the essence of the “vintage” Flatt and Scruggs sound – including Josh Graves’ historic and wonderful Dobro work. I think the fact that the Earls Of Leicester Project/CD won a Grammy Award for Best Bluegrass Album demonstrates there is still a love and yearning for “vintage” bluegrass music, instruments and Dobros.

Music is an art form and I feel that the prewar Dobro including the sound it produces is an art form too and there is still a love for that vintage sound of the prewar Dobros. There are many great sounding prewar Dobro’s, but others can sound very weak and poor. One of the main problems with a lot of prewar Dobros is the lack of volume, which the excellent contemporary builders have largely overcome. If you can’t hear it, you can’t appreciate it and most of us know that often a prewar Dobro was difficult or impossible to hear in even a small jam session. And frequently the tonal qualities were limited by the huge inconsistency of the mass produced stamped cones that were installed in most prewar Dobros along with the lack of proper set up. So, in answer to your question about the difference between prewar Dobros and the resonator guitars built by the contemporary builders, I will start by stating that there are a number of items that we can identify including workmanship, volume, tone, feel, body depth, cone design and quality, peghead configuration, solid vs plywood construction and so on.

The prewar Dobro was a mass-produced item and many were great sounding instruments, but just as many were not. They were made to make money for a company whereas, in almost all cases, today the fine instruments made by the contemporary builders are built for the love of the instrument as the primary motivation and the monetary aspect is there but it is secondary. And, by increasing the body depth, controlling the fit and quality of the wood construction and the addition of a modern handmade spun cone the volume of the new resonator guitars easily surpass the unadjusted prewar Dobros. Also, by building the new instruments with a very high nut and high spider inserts made possible by a new coverplate design with a higher handrest, the volume and feel is also enhanced. The pegheads on newer instruments are typically solid which most folks feel are easier to change strings that the early prewar Dobros with slotted pegheads. Of course, around 1936 several prewar Dobro models were starting to be made with solid pegheads including the classic Model 37 made by Regal that was used by the Dobro greats Josh Graves (after he retired Julie, his 1930’s Model 27), Mike Auldridge and Jerry Douglas in the earlier years of their careers. And many folks feel that the use of solid wood in the modern resos as opposed to the laminated wood used in all the prewar Dobros enhances the sound. However, there are several excellent modern models made by Paul Beard and Ivan Guernsey, among others, with laminated wood which compare very favorably with the solid wood models. Also, the bodies of the early prewar Dobros produced were quite thin which limited the bass response. But when Regal started making Dobros they subcontracted out the construction of the bodies and their supplier happened to make the bodies considerably thicker. This produced a superior low end sound and enhanced the volume. Soon after this the California Dobros began being produced with thicker bodies and eventually by the mid 1930’s both the Regal and the California operation were producing a fine sounding Dobro with nice highs and fuller lows.

1934 Model 27 Dobro made by Regal (from DOBRO ROOTS)

1936 Model 37 Dobro made by Regal (from DOBRO ROOTS)

1934 Model 45 Dobro made in California (from DOBRO ROOTS)

Over the years I have been experimenting with improving the volume and sound of prewar Dobros to bring out the fullness of sound they were capable of producing. I always felt that in spite of the lack of high quality workmanship necessitated by the mass production process that there was a lot more sound and tone that could be produced by them. And I believe I have finally found several enhancements which can make many prewar models compare favorably in volume and tone with newer resos without losing the essence of the vintage prewar sound. They are relatively simple enhancements that can be added and removed, usually in less than an hour, without altering the original instrument’s construction. I will be looking for a way to disseminate this information sometime in the near future.

SJ: Does anyone really know the backstory of how/why John Dopyera and his brothers invented the dobro? The only thing I know is that they were trying to make a louder guitar. I’m curious to know if there are any anecdotal stories of how they came up with the original design for their instrument and whether they experimented with different designs and materials along the way.

Photo of John Dopyera, inventor of the Dobro (from DOBRO ROOTS)

ST: John Dopyera was primarily attempting to make a Spanish guitar (as they referred to a regular six string guitar) louder so it could be heard in large settings or with many other band instruments and to do likewise for the Hawaiian guitar which was extremely popular in the early 1900’s. He was the actual inventor of the Dobro guitar and his brothers assisted in various aspects of the business and production. He invented the tricone guitar first which was produced under the brand name National in the mid 1920’s and then invented the single cone Dobro in about 1928.

John definitely experimented with many cone and material configurations before coming up with the National Tricone metal guitar that he always felt was his best achievement. John and the other Dopyera Brothers all worked for and were part owners of the National String Instrument Company but, after a dispute with his partners, John left National in 1928 and began producing the Dobro in 1929. His brothers joined him and they chose the name Dobro taking the “Do” from Dopyera and the “bro” from brothers to form the word Dobro. In addition, the word “dobro” meant “good” in their native Slovak language.

SJ: Does anyone know how the Dopyeras came up with the Dobro brand logo?

ST: The logo apparently came from a modification of the form of a Lyre, an ancient stringed musical instrument. In fact, the logo includes an image of a lyre and to that they added the letters “DOBRO” and created the now famous Dobro logo. Even the Dobro guitar itself was designed to emulate somewhat the shape of a Lyre which is where the 3 holes at the end of the fingerboard (on most prewar Dobros) came from.

Very early Prewar Dobro Logo with gold border

SJ: Can you give us a thumbnail sketch of Dobro Roots? I believe you’ve concentrated on wood bodied pre-war instruments only. Is there some sort of timeline to help a newbie understand the history of the Dobro company, the different models they offered and the relationship between the Dobro company and Regal? Lastly, was there any overall quality difference between instruments made at the original dobro factory in California vs. the Regal factory in Chicago?

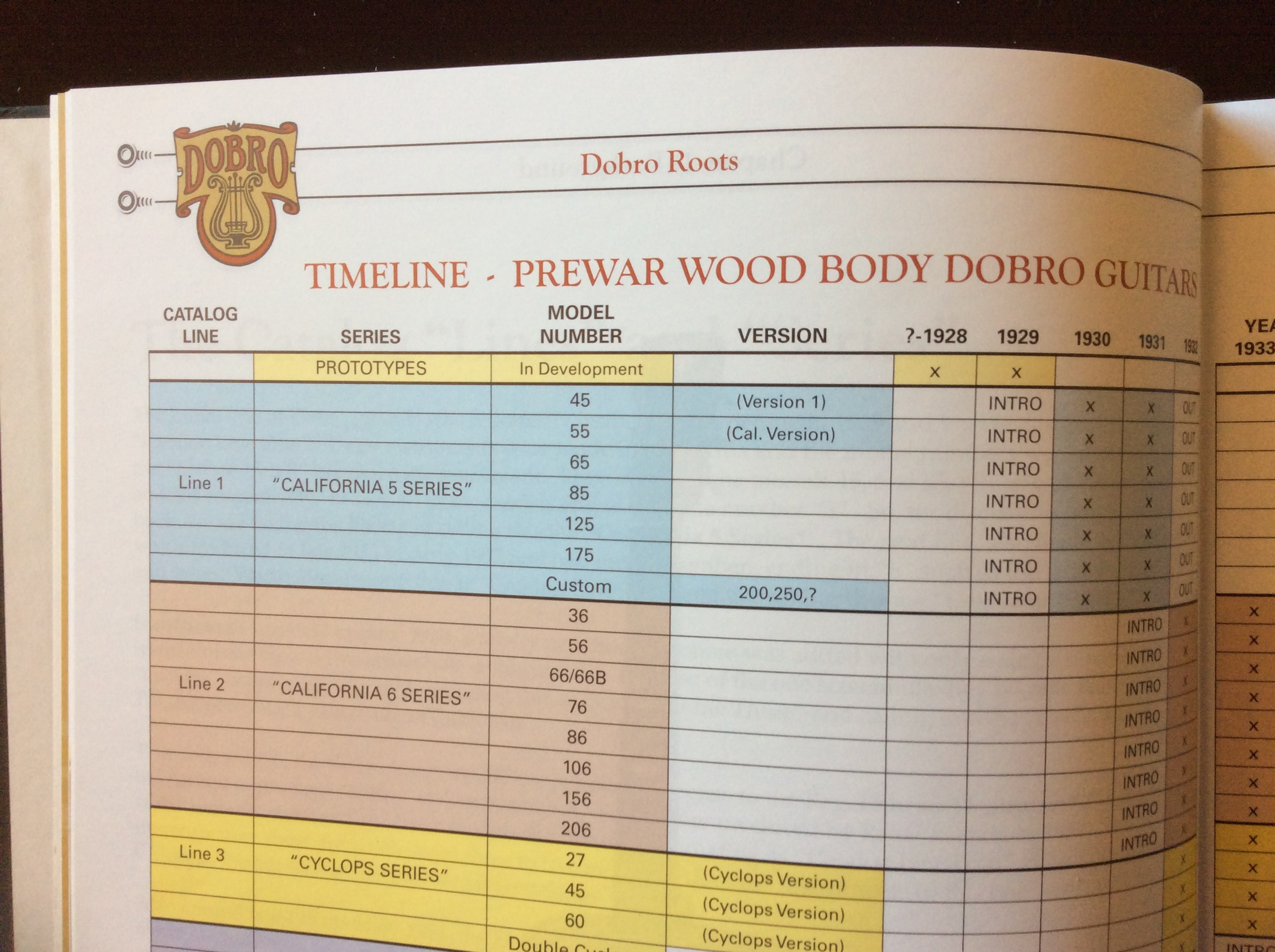

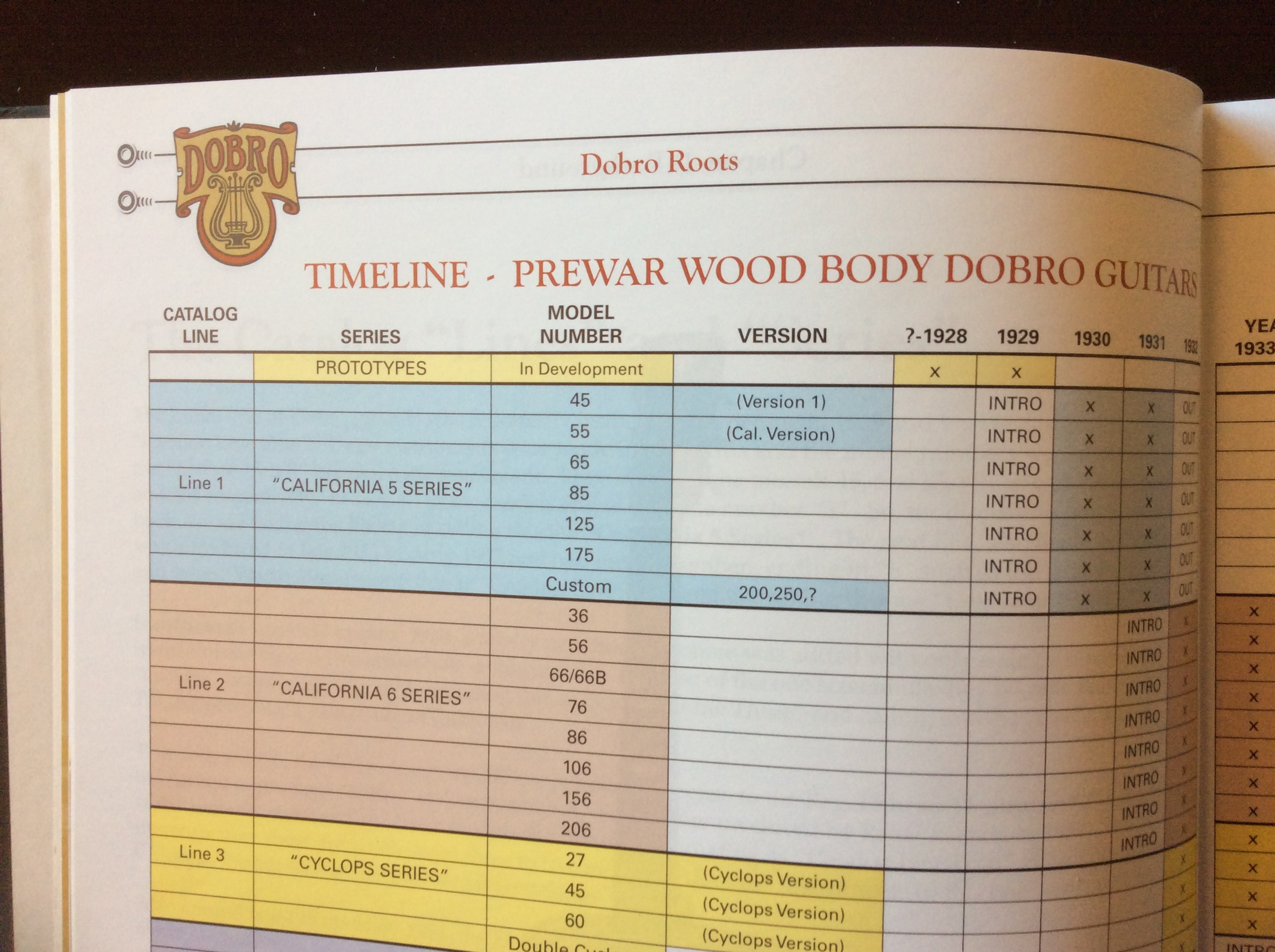

“TIMELINE” of different prewar models offered by Dobro (from DOBRO ROOTS)

ST: DOBRO ROOTS starts out just like the title says – “DOBRO ROOTS” – A Photo Tour of Prewar Wood Body Dobros”. But it’s more than just a tour, it’s a tour in chronological order by model and follows each catalog series in the order they were released back in the 1920’s, 30’s and 40’s. It also includes details of the various models including dimensions and anecdotal details including old catalogs showing the various Dobro lines. I have also created a numbering system for the various lines and I designate them as separate “Series”. For instance, the first line to come out in 1929 had each model ending in the number “5”. It had the Models 45, 55, 65, 85, 125 and 175 so I call this the California 5 Series since these were all made in California by the Dopyera Brothers. The next line had model numbers ending in “6” so I call this the California 6 Series. Then, around 1933, Dobro issued the Regal Co. in Chicago the right to produce and sell Dobro instruments east of the Mississippi River. The initial line of instruments that Regal produced I have designated the Regal First Series.

Each instrument in the book is displayed from original, high quality photos of actual prewar Dobros from my collection, the collections of a few friends of mine and a few borrowed instruments. We did a photo shoot on the west coast for my collection and a shoot on the east coast for my friends’ collections and the other instruments there. We then selected the best of the photos to use in the book. I also created a “Timeline” showing in a two page spread each Series and the various models in each versus a time scale showing the years when each was first offered and when it was phased out. This is the first time this type of information has been shown anywhere in this format which, hopefully, clarifies a lot of this information for readers, collectors and dobro enthusiasts. I based a lot of the information on the serial number data in George Gruhn’s great book “Guide to Vintage Guitars”, Third Edition. So the reader/user of the book has three key sources of information – first: a chart with Series’ designations, models and years; second: actual vintage catalog cuts showing the instruments and; third and primarily: high resolution photos of the actual prewar instruments as they exist today!

SJ: The photography in DOBRO ROOTS is outstanding! It’s truly a treasure chest of different vintage guitars! As a player, I’m curious to better understand the differences between the sound and playability of the different pre-war guitars in the book. For example, do the fancier, more expensive models play and sound better than the less expensive models or are the differences primarily cosmetic?

ST: Thank you for the nice complement on the photography in DOBRO ROOTS! But, I have to thank my two wonderful photographers, Anthony Donez and Ryan Collerd, who produced those great high resolution photos!

As far as sound and playability go, it’s a very interesting and unique fact that Dobros don’t follow the norm of higher price meaning a better sounding and playing instrument. As a matter of fact, it was just the opposite with Dobros! One of the best sounding prewar instruments, in the opinion of many experts and many of the great dobro players, was the low end Model 27 that was made of birch plywood. In addition, the Model 27 was a no frills instrument with binding only found on the top of the body, an unbound neck, simple tuning machines and an “ebonized” fingerboard of non-descript wood.

1932 Model 156 Dobro made in California (from DOBRO ROOTS)

On the other hand, the beautiful high end walnut laminated models, such as the Models 125, 156, 175 and the very rare Model 206, left a lot to be desired as far as sound was concerned. Although all the prewar Dobros were made of plywood or laminated wood it seems that the type of wood used – whether walnut, spruce, mahogany or birch, did play quite a big role in the sound that the instrument produced. Sure, the cone was the primary vibrating element but the wood also contributed greatly to the sound too. And playability seemed to mostly depend on who was on the assembly line at the set up stage of the final product. Although, in general, the higher end models did seem to have more attention paid to a good set up job than the lowly Model 19, 27 or the 37.

SJ: I have to admit I know next to nothing about prewar Dobros so if you don’t mind I’d like to get clarification on a few things: Were all prewar Dobros made with a soundwell? What was the function of the soundwell in the design of the instrument?

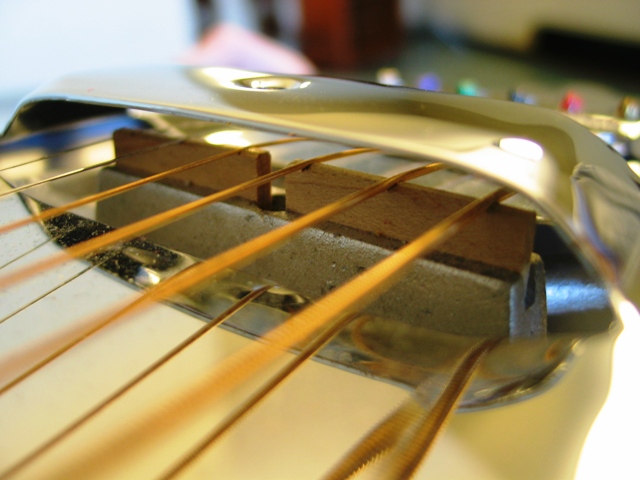

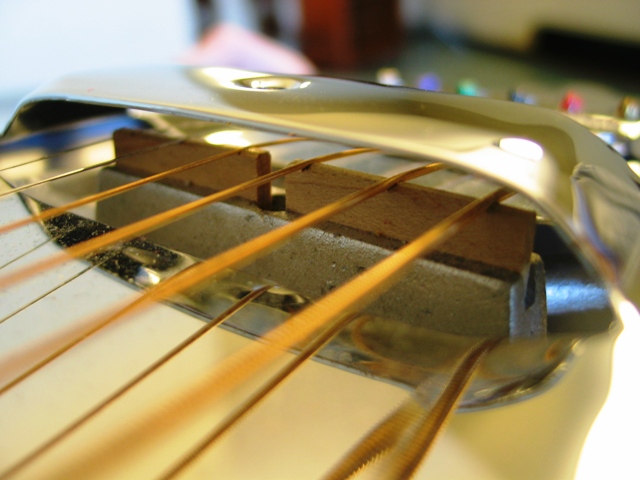

Prewar Dobro Soundwell

ST: No, not all prewar Dobros had soundwells. (By the way, for those not familiar with the term, I should mention that the soundwell was a ring of plywood running in a circle between the top and back of the body almost directly under the outside rim of the resonator cone.) Most prewar Dobros with round screen holes did have soundwells but some lower end instruments were produced with no soundwell apparently as a cost cutting measure. In addition, most f-hole models had no soundwell. The soundwell usually had holes in it, either round or parallelogram in shape, although a few have been seen with no holes at all.

The soundwell was primarily installed as a positive support for the resonator cone but it also acted to transmit the vibrations of the cone into the back of the body as well as the top. Modern open-body resonator guitars have soundposts to act in place of a soundwell. The prewar Dobros without soundwells had either a thicker one-half inch thick top or an extra wood ring just under the outside rim of the cone.

SJ: What’s the difference between a stamped and a spun cone in a prewar Dobro? Does one sound better than the other?

ST: A stamped cone was made from a sheet of aluminum that was stamped into the conical shape of the cone. A spun cone was made by placing the sheet of aluminum in a machine that would spin against the sheet forcing it into the conical shape. The prewar spun cones, especially those made in the later 1930’s, seemed to be more consistent in shape and thickness and that led to a more consistent and better sound. The stamped cones, on the other hand, were very inconsistent in thickness and had many ripples in them caused by the stamping process. This led to the sound being very inconsistent with some sounding great with bright highs and nice lows while others were thin sounding with almost no low end at all. In most cases, I prefer the sound of a modern spun cone installed in place of an original stamped cone whereas an original spun cone often sounds as good as a modern cone. But a good stamped cone has a wonderful old time“prewar” sound that can’t be matched by a modern spun cone. But, the sound of an instrument is very subjective especially when it comes to prewar and modern dobros and spun versus stamped cones.

SJ: What kind of materials did the factory use for bridge inserts and nuts? I’m assuming they used maple bridge inserts and a plastic nut, but I’m not 100% sure. Most, if not all of the vintage Dobro’s that I’ve played have been in dire need of a good set up. Is that a function of normal wear and tear over decades of use or has the notion of a good set up on a dobro changed over time?

Bridge inserts on prewar Dobro – typically the inserts on a factory standard setup guitar were seated too low to create enough tension on the cone to maximize the volume potential of the instrument

ST: The spider bridge inserts, I have been told, were made of boxwood which is a very hard wood, probably harder than maple. And based on my observations the nuts were made of bone. However, the original set up of most prewar Dobros was very inconsistent and the inserts were typically much too low to drive the sound fully into the cone. And the nuts were also quite low compared to modern set up dimensions. So, it was a combination of inconsistency and the evolution of good dobro set up characteristics that hampered the prewar dobros from sounding as good as they could have sounded based on overall construction.

An interesting thing about prewar Dobros is that often they were played very little! They were most likely purchased with good intentions of learning to play Hawaiian music in the case of squareneck Dobros or western or jazz music in the case of round neck Dobros but the learning process never took place. So you can often find prewar Dobros in great condition most likely because they were stored under a bed, in a closet or an attic soon after the purchase was made.

SJ: What is the story behind the Cyclops model? How do the Cyclops models compare to other prewar guitars in sound and playability?

1933 Dobro Cyclops Model (from DOBRO ROOTS)

ST: The Cyclops Models were brought out in the middle of the Great Depression around 1933 apparently as a cost cutting measure. They were able to eliminate one of the two round screens. And, in the case of the Double Cyclops models the two holes were reduced in size and moved together so they could be made out of a single piece of metal covering a single hole in the body. Also, the Cyclops Dobros often had no soundwell to save on cost but they did have the one-half inch thick top. But, I came across a sandblasted Model 60 Cyclops with both a soundwell and a thick top which also sounded surprisingly good. But, in most cases, the sound of the Cyclops models did not compare favorably to the two openings with screens to allow more sound transmission out of the upper bout. So the Cyclops Models were a short lived line that was phased out within a year of introduction.

SJ: What is the function of the 3 small holes just below the fingerboard in some of the models?

ST: The 3 small holes at the end of the fingerboard were purely artistic with the intent of copying the appearance of a lyre! The holes serve no purpose as far as sound is concerned and were omitted on the Model 27 and most Model 37s around 1934/1935.

SJ: What is a lug cone? What is a short spider?

Short Spider and Lug Cone

ST: Both of these questions are directly related so I’ll answer them together. The lug cone was developed to provide a support position for the “short” spider bridge. The first Dobros produced had a long spider bridge that rested on the outer lip of the cone. But, after a few years they introduced a short spider that did not reach the outer lip. So a stamped cone was developed with 8 indentations or lugs, as they became known, to provide support points for the shorter legged spider bridge. I believe that this short spider and lug cone system was developed to produce a brighter and more brilliant sound with some additional volume from a Dobro. Apparently, the initial system was found to be lacking in volume and treble sound. Surprisingly many prewar Dobros can be found with a lug cone and a long spider! They did a lot of strange things back in the days of the prewar Dobros.

SJ: Was the idea behind a slotted headstock on some of the models to create a greater angle break behind the nut and increase the volume and projection of the guitar? My first dobro was a model 60D with a slotted headstock and I used to hate changing strings! (laughs).

Prewar Dobro Headstock

ST: I believe the slotted headstock was used since it was the norm used on Spanish type guitars of that period. As far as I know, it had nothing to do with increasing the break angle at the nut. It wasn’t until tuning machines became economically available in approximately 1936 that Regal began making Dobros with solid headstocks. And when production of Dobros was started again in the 1960’s they were once again made with slotted headstocks in an attempt to replicate the original instruments of the prewar period. And, although changing strings is somewhat more difficult on a slotted headstock Dobro, it took the O.M.I. Company in the 1970’s several years before they started producing solid headstock instruments once again.

SJ: You’ve amassed an amazing collection of prewar Dobros over the years. I’m curious to know – do you have a favorite instrument? What have been some of the highlights of building such a nice collection of vintage Dobros over the years?

ST: It’s interesting and probably surprising that I really don’t have just one favorite Dobro. I seem to go in phases where I’ll play a certain Dobro for a period of time, say several months to years and then switch to a different Dobro for another time period. And at times I just switch back and forth depending on the gig and the type of music I’m playing.

Some of the highlights of obtaining my collection include finding my first Dobro, a Model 55 roundneck, and then, my second one, a square neck Model 37 Dobro made by Regal with a solid headstock very similar to the one on the wonderful classic Mike Auldridge Dobro album. And I still have both of them! Then another interesting one I purchased was a Model 125 Custom gold plated engraved round neck that Bobby Wolfe had pictured in his great book The Resophonics and the Pickers. After Bobby had sold it, I came across it by accident on the internet at a store in the Netherlands where they called it a Model 256, a model which never existed to my knowledge. But, when I received pictures of it, I recognized it as Bobby’s former Dobro. I jumped at the occasion and when it was delivered, UPS left it at the front door of the wrong house in my neighborhood around the corner from where I lived. But the tracking info said it was delivered so I went searching for it and found it just sitting there unattended near a neighbor’s front door. I just picked it up and took it home with no problem! And it was shipped in its case wrapped only in bubble wrap with no outer carton! It was the most unique delivery of one of the most unique Dobros I own. In fact, it is the Dobro on the cover of Dobro Roots!

And, of course, when I was alerted a few years ago by a friend back on the East coast that Gruhn Guitars had a 1932 Model 206 round neck for sale, I jumped on it and was able to purchase a Dobro I never in a million years thought I would one day own. It even has the original gold spider and gold stamped non-lug cone of the period. And since only three are known to still exist and the neck is quite straight I have only played it as a Spanish guitar. And it plays and sounds wonderful that way! So, I’ve never put a high nut on it to play it Dobro style so I can retain the neck in its near original condition. Although the cover plate gold is mostly worn off, it does have the pearl tuner buttons and gold sparkle binding, the spruce top and walnut back, sides and top.

SJ: Any closing comments for our readers?

ST: Well, I guess I would say that Dobros and all resonator guitars are wonderful, unique, and very different instruments. And the Dobro guitars from the prewar period (1929 to 1941) were the roots from which sprouted many limbs and branches, that is, the variations on the original design of John Dopyera together with the production work of his brothers. And just as there are a variety of sounding prewar Dobros there are also a variety of sounding post war (late 1950’s through today) Dobros and resonator guitars. Each is somewhat different and there is not one that is suited to every player, listener, collector or fan and there is not one that is necessarily better than any other. They are merely different just as the music that is played on one differs with the player, the musical genre, the surroundings, the playing style, the techniques used to make it sing and so on!

But there is one thing for sure, the prewar Dobros produced by the Dopyera Brothers in California and the Regal Company in Chicago can never be reproduced! There are a limited number of originals and there will never be any more. I guess that’s part of the reason I love to play them, collect them and look at them like works of art from another era. And if you are a dobro player and have never played a properly set up prewar Dobro, you owe it to yourself to give one a try, if you can find one. Happy hunting and have fun!